So where do patents come from? It’s all very well saying, “Go and write some patents,” but where do you start? How do you come up with ideas that are new, useful and non-obvious? To illustrate the different ways in which this can happen, here is the background to a few of the patents that DataCore have filed on our journey to defining the boundaries of software-defined storage.

Collaboration

One particular Thin Provisioning patent was borne out of a long transatlantic telephone conversation with DataCore’s CTO, Roni Putra. We’d been given a design proposal for an idea that was much like a traditional filesystem; it managed blocks of data and split them down into smaller fragments. The more we discussed the idea, the more problematic it seemed. Filesystems are notoriously difficult to get right, and the complexity of the design was likely to tie us up in years of development effort.

As we debated what we could do instead, we realised that file sizes had been growing larger over the years and that storage capacities were increasing to match. Whereas, previously, wasting a few KBs of disk space was a big issue, now, wasting a few MBs only made a nominal difference to the overall utilisation. From there, it was a short step to a design that divided the storage up into large fixed-size chunks and mapped them to individual volumes using a simple array. There were lots of details to follow up on, for example ensuring that the data structures could withstand a system crash, but the heart of the design was thrashed out in the collaborative “back and forth” dialog.

Often the best ideas are worked out as part of a team. If you have an idea that you think might be worth investigating further, then talk to people about it and involve them in exploring the design with you; don’t assume that you have to get every detail nailed down first!

Inspiration

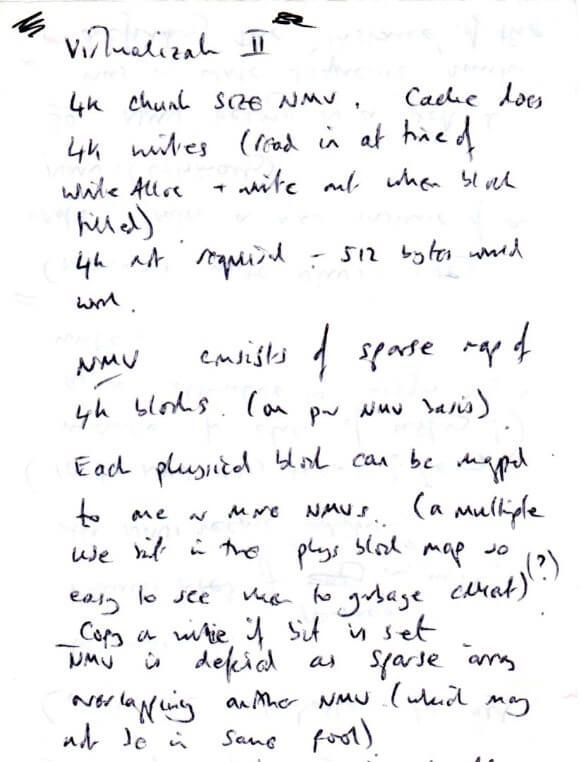

Sometimes the best ideas happen in the least likely places. I remember standing in the shower in Fort Lauderdale, thinking about Thin Provisioning and how it would be interesting, but impractical, to make it work on a 512-byte block basis, when a “light bulb” moment occurred. What if we assumed that every write was at least 4k in size? Suddenly, an impractical design started to look an order of magnitude easier!

The “light bulb” moment wasn’t a patentable design, but even without being able to see the details clearly, it created hope and a sense of excitement that there was something there that was worth exploring further. The rest of the day was booked as time off, and I remember wandering around Sawgrass Mills, a large shopping mall, with my family, pencil and paper in hand to jot down additional thoughts as they occurred. In fact, I’ve still got the piece of paper; it represents the start of a journey that lead to a series of patents for Continuous Data Protection and the fine-grained data mobility that we plan to deliver in the future.

Give yourself space to let your mind wander; sometimes it’s only when you stop staring at a problem head on that you’ll really see it for what it is. Don’t be put off if you only have a glimmer of an idea; learn to recognise the sense of excitement that can mark the start of a breakthrough. Above all, don’t let practicalities drown out great ideas. The original patents seemed resource hungry, but not when compared to the power of today’s systems!

Perspiration

It’s not glamorous, but sometimes patentable ideas come from long hours of persistent slog. The first step is to really understand the problem; to wrestle with it and look at it from different directions until you can build a comprehensive mental picture of what you are trying to solve. Then the hard work begins; trying solutions against the model and seeing how they stack up, refining them and repeating, discarding them and looking for new approaches. Exhilaration can quickly be followed by despair, as yet another attempt fails.

Working on multithreading changes as part of obtaining world-record SPC1 benchmark results, I remember wandering around Clearwater Marine Aquarium with my family looking at Winter and Hope from the film Dolphin Tale. I may have been physically present with them, but in my mind, I was continuously running experiments on the code to see how we could move the bulk of the locking out of the main path. In all, I think it took about a week to come up with a satisfactory design.

Learn to be persistent. If your ideas don’t pan out first time, keep on trying; you learn something from each failed experiment. There is a time to let go and move on, but it’s probably a lot further out than most of us think!

Conclusion

We all share responsibility for generating Intellectual Property for our employers. Sometimes that will be through writing code, but sometimes there will be ideas that are worth pursuing as a patent application. If you have ideas, speak up and see where they take you!

If you’d like to see how the innovations I’ve described have turned out as real-world products, then why not try SANsymphony or a hyperconverged virtual SAN from DataCore, the authority on software-defined storage?